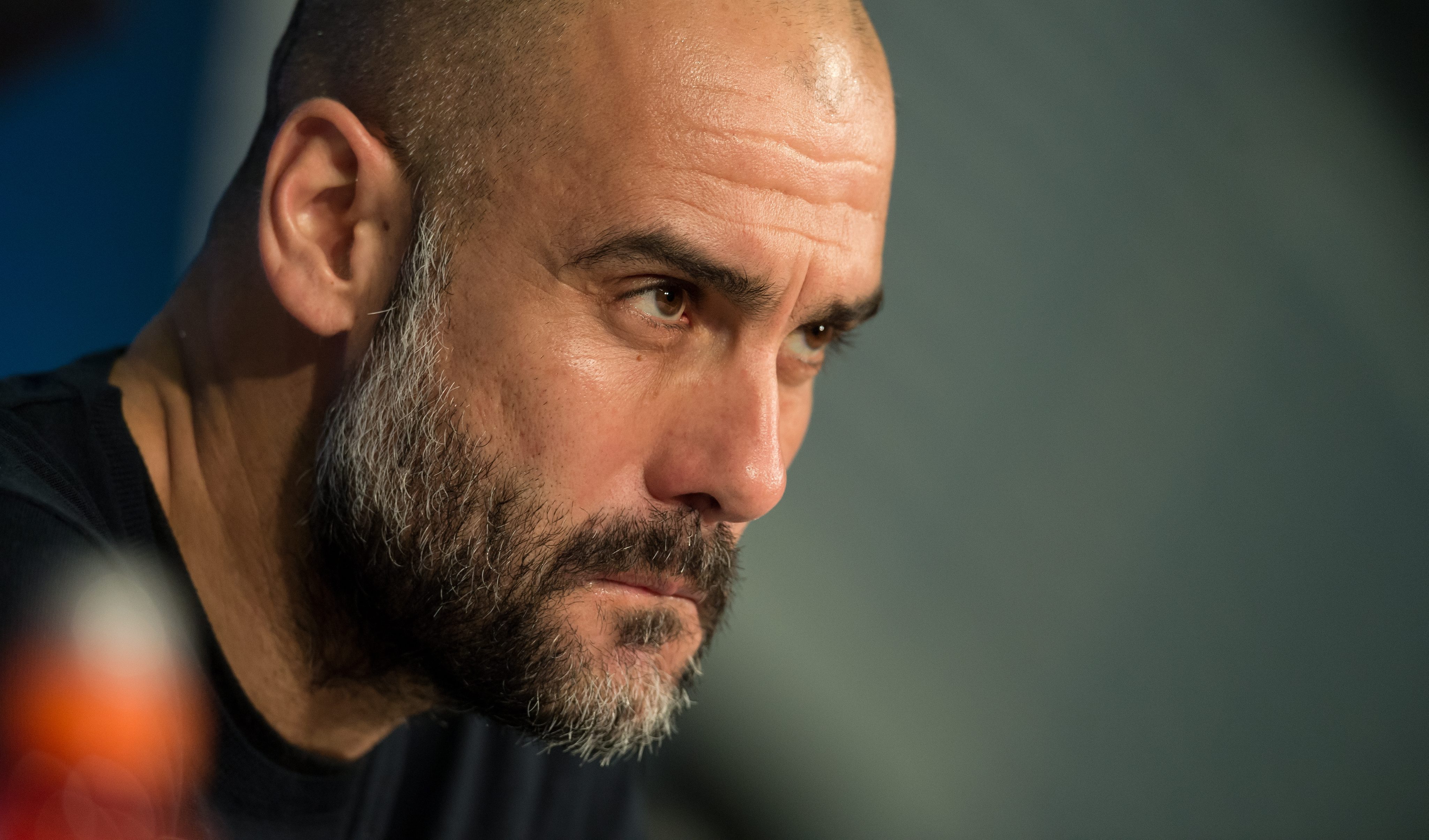

Pep Guardiola bids farewell to Germany in the coming days and the debate over whether or not his time at the Allianz Arena was a success rages inexorably on.

Three Bundesliga titles, a DFB-Pokal triumph, a FIFA Club World Cup and a UEFA Super Cup. Not too bad for ‘failure’ — the label some in the football world have given Pep Guardiola’s time at Bayern Munich because of his three consecutive semi-final losses in the UEFA Champions League. To assess the Spaniard’s time in Bavaria through the binary prism of ‘success’ or ‘failure’ based on the team’s Champions League performance is to willfully ignore the fact that winning the Champions League was quite obviously not Guardiola’s only remit. Nevertheless, despite its fallacious logic, this false dichotomy has been propagated by a surprising number of journalists, pundits and fans in recent weeks as Guardiola prepares to wave goodbye to Germany.

It would be fair to say that Bayern have fallen short in the Champions League. However, to judge Guardiola’s body of work at the Allianz Arena over three years based on a knock-out competition where so much is down to chance is, quite simply, absurd. The yo-yoing of opinion regarding the former Barcelona coach’s managerial prowess borders on parody, to the point where a Thomas Mueller equaliser makes Guardiola a ‘genius’ (Bayern’s win over Juventus), while the same player missing a penalty makes him a ‘fraud’ (Bayern’s aggregate loss to Atletico). These moments – like Saul’s virtuoso goal at the Vicente Calderon — are largely beyond the manager’s control and are indicative of how slim the margins are in the Champions League, particularly in the latter stages of the competition.

One of the more common accusations levelled at Guardiola during his time at Bayern was that the Spaniard chose an ‘easy job’, a belief that has also spawned the notion that Guardiola still has something to prove – that he needs to achieve something with rank underdogs in order to prove his quality as a manager. Sun journalist Anthony Kastrinakis perhaps best summed up this general sentiment recently when he demanded, “But could [Pep] do a Claudio Ranieri?” Almost certainly not. But could Claudio Ranieri do a Claudio Ranieri again? Almost certainly not.

It is impossible to define ‘success’ in absolute terms, just as there is no absolute scale to determine the ‘difficulty’ of a job. The expectation of a club from its manager, a crucial element of this discussion, is so often ignored. Learning a new language and taking over a Bayern team that recorded one of the best seasons in the club’s history was difficult not only because Guardiola had to adapt to a different culture, but because the 2012-2013 season was the yardstick by which he was judged. His mission: win everything. Anything less and it is failure. That level of expectation meant that Guardiola’s job was difficult – not necessarily more difficult or less — in a different sense to that of, say, a manager tasked with avoiding relegation.

Thankfully, there is still room for nuance in public football discourse, and as journalist Raphael Honigstein pointed out in his recent ESPN column, Guardiola has achieved much of what Bayern hired him to achieve, leaving behind a great team and a solid foundation for Carlo Ancelotti to build on.

His work at Barcelona – seen by some as ‘easy’ due to the quality in the squad – had a transformative effect on the team and the club as a whole, and Barcelona’s recruitment process, described in wonderful detail in Graham Hunter’s book “Barca: The Making of the Greatest Team in the World”, provides insight into how difficult the decision was for the club and Guardiola himself. Pep reportedly asked Marc Ingla, the vice president of football for Barcelona at the time, “Why don’t you hire Mourinho? It will be easier for you.” It would have been, just as it would have been easier for the then relatively inexperienced Guardiola to not stake the reputation he had at the club by taking over a Barcelona side suffering greatly from the insidious effects of Frank Riijkard’s final months in charge. Guardiola risked it all and succeeded like no one before him had.

Amusingly, Pep was also accused of taking the ‘easy option’ after his Manchester City appointment was made public, by a minority that is now rapidly disappearing. City have done their best to contest that argument with their form in recent times, but the difference, again, is the heightened expectation at a club like Manchester City, where he will be expected to win the Premier League and deliver a Champions League trophy. What is true, however, is that Guardiola will not have – at least to begin with – the same raw materials at City as he did at Barca or Bayern. The Citizens have a good squad, but not one that compares to Europe’s elite.

Manchester City job Guardiola’s toughest challenge yet

“I’m sorry, but sometimes we talk too much about the coach,” Pep said when shown a video of Arjen Robben’s goal in Bayern’s 5-1 win over Arsenal in the Champions League and asked whether that was a move the team practised in training. Speaking at the fan event, the Bayern boss went on to say, “Of course all managers do their best, but it’s the quality of the players. A good manager cannot win without the quality of the players, but good players can win with a scheiße manager.”

Although there was an element of entertaining the crowd in that quip, it was obvious that Guardiola’s point was an honest and serious one. The quality of the players, then, is what Manchester City don’t have in comparison to the best teams in Europe – something that was not an issue for him at Barca or Bayern. The presence of Txiki Begiristain and Ferran Soriano, two men who were also crucial to appointing him at Barcelona ahead of Jose Mourinho, will undoubtedly aid Guardiola in his City revolution, but the magnitude of the task cannot be overstated.

Whether you consider Guardiola a pioneer, a revolutionary, something in between or indeed neither, it cannot be denied that his time at Barcelona was almost solely responsible for introducing ‘tiki-taka football’ into the modern fan’s lexicon. In a sense, that has proved to be a negative during his time at Bayern, where many have inexplicably accused him of tactical inflexibility or pronounced the death of tiki-taka football, when in reality Pep’s Bayern have a very different style to Pep’s Barca. The focus on possession and position is an obvious parallel, but around that framework, Guardiola has developed a side at Bayern capable of attacking in a variety of ways, as was obvious in the semi-final against Atletico Madrid or in the demolition of Borussia Dortmund at the Allianz Arena earlier this season.

Another small but fascinating glimpse of this variety is evident in Guardiola’s explanation of his team’s setup in a 2-0 win against Hertha Berlin in November 2015. Hertha lined up with five defenders and Bayern were missing wingers Arjen Robben, Douglas Costa and Franck Ribery. Pep sought to stretch the Hertha defence by having his full-backs provide the width, instructing the likes of Jerome Boateng, Javi Martinez and Xabi Alonso to play the ball to them while the likes of Thomas Mueller, Arturo Vidal, Robert Lewandowski and Kinsley Coman loaded the box to try and convert crosses. Although not by any means a particularly clever or extraordinary ploy, it should serve to underscore the fact that Bayern’s football under Guardiola has been nothing like that of his Barcelona side.

While Barcelona largely passed the ball through the centre of the pitch given the quality of players like Xavi and Iniesta, hypnotizing their opposition like snake charmers before striking like a snake when a gap opened up in the defensive line, Bayern’s attacking under Guardiola has largely been about their clever use of width. Due to the qualities of the players at Pep’s disposal, the Allianz Arena has seen more direct football and more individualistic play from the likes of Arjen Robben and this season, Douglas Costa.

However, the foundation for the attacking football at both Bayern and Barca has been the build-up play from the back – which brings us back to Manchester City. Guardiola will not have centre-backs who have great quality on the ball when he arrives at the Etihad. In fact, City have been exposed numerous times throughout this season because the likes of Eliaquim Mangala and Nicolas Otamendi have given away possession in dangerous areas of the pitch.

More crucially though, City do not have a pivote – a player like Sergio Busquets or Philipp Lahm or Xabi Alonso who can sit deep and distribute intelligently. Yaya Toure, Fernando, Fernandinho and Fabian Delph each have their strengths, but none quite fit that description. In David Silva, Kevin De Bruyne and Sergio Aguero, Guardiola has an attacking core that he can work with and improve, but fixing the rest of the side will take time and presumably, a significant amount of money.

Beyond just the tactical side of things, Guardiola will also have to contend with playing more games in the season without a winter break and the ever-increasing competitiveness of the Premier League, where the likes of Manchester United and Chelsea in particular are likely to come back stronger, armed with new managers and fresh optimism.

A short-term coach with a long-term impact

An aspect of Pep Guardiola’s management that is rarely talked about is the sheer intensity that he demands from himself and his players in training as well as during the game. Intensity is – perhaps subliminally – associated more with defensive football, meaning that it is often an adjective used for teams managed by the likes of Jose Mourinho and Diego Simeone. However, Guardiola’s training sessions have gained notoriety for their intensity, with David Alaba on one occasion describing them as ‘incredible workouts’.

This YouTube clip of a Bayern pre-season training session is a fascinating insight into one such workout, with the team practising an attacking move starting with Bastian Schweinsteiger in midfield and involving Philipp Lahm as the central focus. A frothing Guardiola is seen shouting himself hoarse and moving around like a madman, demonstrating every movement with fervour and ordering his team to repeat it until they begin to get the hang of it. A couple of ‘Bravos’ later, Guardiola consults his notebook and asks players to change position, presumably to do it all again.

It is not difficult to see, then, why Guardiola is a short-term coach. And that is not necessarily a disparaging term even though it is viewed as such by many. Quite simply, his style of management is – much like Mourinho’s – palpably draining. Pep brought his time at Barcelona to an end after four seasons, but admitted he knew very early into his final season that he wanted a break, and he communicated as much to the club board. He looked then, as he does now, ready to recharge his batteries for a new challenge.

Guardiola’s impact though, is anything but short term. At Barcelona he assembled one of the greatest club sides in history and laid a foundation for future managers to build upon. Meanwhile, David Alaba has been among the most vocal admirers of Guardiola during his time at Bayern, revealing that he never knew he could play in so many positions before the Catalan coach came along. Football journalist Gabriele Marcotti wrote in a recent ESPN article that the Bayern hierarchy believed Guardiola had introduced ‘concepts and an evolution’ that had improved the club.

It is difficult to recall the last managerial signing in the Premier League that was as highly anticipated as Pep Guardiola’s. Manchester City are an ambitious club wishing to be in the same bracket as Europe’s crème de la crème, and appointing the 45-year-old will prove to be an educational process for both players and the club that will likely get them much closer to where they want to be.

“What did you learn, idiot, to kick the ball better?” Sergio Aguero jokingly asked his close friend Lionel Messi when the Barcelona icon revealed that he had learned a lot from Pep Guardiola. Manchester City’s hitman will have his answer very soon.