The origin of football in India can be traced back to mid nineteenth century when the game was introduced by British soldiers and sailors. While we have rarely been completely up to date with prevalent tactics of modern football, Indian football has gone through its fair share of tactical revolutions. In this series, we will make an effort to track down the tactical evolution of Indian football.

1) Early Era – Profiling three great 2-3-5 teams

2) First Revolution under Syed Abdul Rahim

3) The Tactical Innovations of P.K Banerjee, Amal Dutta and Syed Nayeemuddin

4) Modern Era – New Generation of Indian Coaches and Foreign Managers

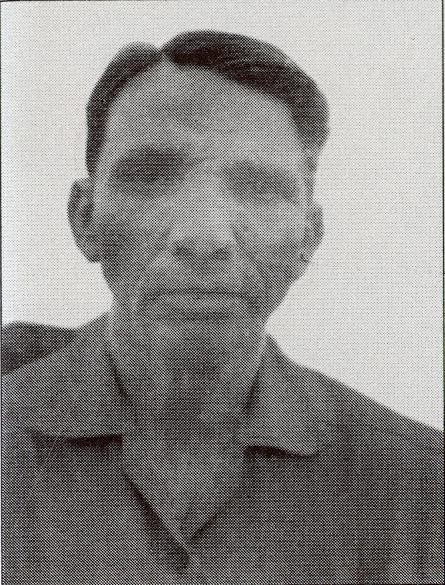

First Revolution under Syed Abdul Rahim

By the 1940s, Indian football gradually got de-centralized away from Bengal. Hordes of skilful players began to emerge from places like Mysore, Chennai and Hyderabad. It was Bangalore Muslims who first challenged the hegemony of Kolkata team while Hyderabad City Police was the first non-Kolkata team to consistently dominate Indian football. In those days Indian Olympic Football teams used to contain a large number of players from Hyderabad while the big clubs from Kolkata also employed players from the city of Nizam. The first tactical revolution in Indian football would emerge from Hyderabad, led by Syed Abdul Rahim – Rahim saab.

Rahim saab’s 2-3-5

After masterminding the rise of Hyderabad City Police as well as Hyderabad in Santosh Trophy, Rahim was employed as the coach for Indian football team before 1951 Asian Games. Rahim saab was one of the few Indian coaches who was fully versed with the changing landscape of International football. He was also a realist who knew that Indian players should not be forced to play a system that they were not comfortable with. Initially he set up his team in the traditional 2-3-5 formation.

For the 1951 team, veterans Sailen Manna and Papen paired up as full-backs. Manna was unarguably the greatest Indian defender in a Two-Back system. He was also famous for his long passes and possessed a fearsome kicking ability despite playing barefoot. He was however, an orthodox defender who rarely ventured out of his half. The class of 1951 also had stalwarts from East Bengal’s five pandavas – Ahmed Khan, Venkatesh and Saleh. Venkatesh’s ability to cut in from the wings was wonderfully completed by Sunil Nandy in the other wing. Nandy was a more traditional winger whose crossing ability was top notch.

The most important piece of the puzzle in the 1951 team was Sahu Mewalal. Mewalal was centre-forward and he had qualities to excel in international level – a rare feature among Indian centre-forwards after him. His heading ability, positioning and courage made him vital to Rahim’s plan. With Mewalal in his team, Rahim could field a conventional 2-3-5 without the fear of his centre forward being ineffective in front of physically challenging defenders. Another key aspect of this team was the interplay between two inside forwards – Ahmed and Runu Guha Thakurata.

Ahmed would often drop deeper as he did with East Bengal while spraying ground passes towards Venkatesh and Nandy – therefore making perfect use of the width and outstretching the two backs of opponent teams. Taking advantage of opponent defenders’ getting out of position, Guha Thakurata would utlise free spaces and launch short crosses towards Mewalal. India’s winning goal against Iran in 1951 Asian Games was scored from a Mewalal header off a Guha Thakurata cross.

Switching to Three-Back System and Withdrawn Centre Forward

Rahim was dazzled by the tactics employed by Gustav Sebes’ legendary Hungary team of the 1950s. He had the fortune of observing the Hungarians closely in the 1952 Olympics. The Magical Magyars as they were called remained unbeaten in a stretch of four years in the early 50s and were easily the best team on the planet at that time. Made up with a golden generation of players hailing from FC Honved, Hungary revolutionised football by introducing the withdrawn centre-forward. Nandor Hidegkuti would start off as a regular centre-forward but would drop down deeper into midfield as the match progressed.

This was the era of man-to-man marking so either of opponent full-backs would try to mark him and get dragged out of his position which helped the likes of Puscas and Kocsis to terrorize the other two full-backs. On the other hand, if the opponent full-back didn’t mark him, Hidegkuti would have acres of space all to himself and he would set up his team mates for goals with precise passing. In that era, this was an unstoppable tactic and no team were able to figure out or counter the Hungarian team.

Hungary’s tactics coupled by the mauling India’s 2-3-5 received against Yogoslavia 3-2-3-2 system (a 10-1 defeat) convinced Rahim it was time to change. Rahim was an admirer of new tactics but he was also a realist. He knew that Indian players were not blessed with the natural ball skills of Hungarians and neither did he have a mobile centre-forward like Hidegkuti in his disposal. However, Rahim did have Neville D’Souza – a man with brilliant close control and a perfect eye for goal.

So instead of using D’Souza as a centre-forward he used his captain Samar “Badru” Banerjee for that role. Banerjee, captain and an inside forward, was a wonderfully dynamic player with good dribbling skills. Banerjee played as a deep lying playmaker instead of a proper withdrawn forward feeding D’Souza. Rahim also successfully transitioned his team from the two back system to three back system. He excluded veteran defenders who were used to playing the two back system and included the likes of Latif and Azizuddin who were in sync with the new system. India performed brilliantly under Rahim’s new tactics in Melbourne Games. After thrashing hosts Australia 4-2, India became the first team from Asia to reach last four in Olympics football.

Rahim saab Plots Jakarta Triumph

Rahim and India’s greatest triumph was gold in Jakarta Asiad in 1962. This tournament tested Rahim’s tactical acumen to its breaking point but the great man triumphed against odds – The Indian team lacked a proper centre-forward in the Mewalal, D’Souza mould. His initial plan was to use Afzal as a withdrawn striker while using the quintet of PK-Chuni-Balram-Yousuf Khan as advanced strikers. Each of these four players were at the top of their game at that point and had their unique traits.

Chuni was the natural leader, the one with sublime dribbling skills and delicate swerves. Balram was a complete footballer, the industrious work-horse who would act as linkman between midfield and strikers. PK was the quicksilver winger who could hit long rangers with pin point accuracy. Yousuf Khan was the all-rounder who could play seamlessly in any position. Afzal failed to cope with the pace of other four strikers and India struggled. Rahim tried using left-out Arunmainayagam in the same role but things didn’t improve.

In the end, an injury to centre-back Jarnail Singh opened a new vista. Jarnail took six stitches on his head so he was unable to play as a central defender. Rahim took a calculated gamble. Having known the fact that Jarnail started his career as a centre-forward, Rahim pushed the Mohun Bagan player up as a striker. This move worked like a charm! Jarnail with his gigantic strides and fearsome headers meshed instantly with the four strikers. However, pushing Jarnail up also meant that India lacked its most feared defender at the back. To cover this, Rahim pulled Arun Ghosh in from his left-back position. Ghosh was a brilliant match reader with precise sense of timing – he excelled instantly in his new position.

To further shore up his defence Rahim dispatched Ram Bahadur – a player with beautiful ball skills but who lacked defensive abilities. He replaced Ram Bahadur with youngster Prasanta Sinha. Sinha, a left-half was instructed to cover a small area on the left side and to act as a defensive screen. Franco Fortunato – a ball winner with never say die attitude was the final piece of the puzzle. Yousuf’s versatility meant that he would often drop down as a full-back covering a Jarnail-less defence. According to veteran journalist Novy Kapadia, this was an early version of 4-2-4 system which would be perfected by Vicente Feola’s Brazil team.

Syed Abdul Rahim’s premature death was unarguably the single biggest set back for Indian football. He was an exceptional coach – a man who knew how to change and when to change. Rahim’s influence on Indian football would remain even after his death. Two players who played under him – P.K Banerjee and Amal Dutta would later go on to become India’s finest coaches.

To be Continued…

Sources: “Stories from Indian Football” by Jaydeep Basu. “Goal-less” by Boria Mazumdar and Kaushik Bandopadhyay. “East Bengal-Mohun Bagan Reshareshi” by Manas Chakravarty. “Ekadoshe Surjodoy” by Rupak Saha. Old articles in Khela Magazine and other news papers.