Some teams are remembered for their tactical innovations, like Rinuus Michel’s Holland side or Arrigo Sacchi’s Milan. Yet there are teams who, despite making important contributions to the game, have gone unnoticed. We take a look at five such teams.

Scotland National Football Team (1872-1903)

Surprised? Don’t be. Whenever you let out a gasp after a seeing a Zidane laser-directed pass or a Xavi through-ball, spare a thought for the first Scottish national team.

England played Scotland in 1872; it was the first international football match in history. Eleven years later, the British Home Championship was started with four Home Nations. Scotland won the first six of seven titles. They rarely lost games, losing just two out of the forty three games played in that period. England, the inventors of the game, struggled against this Scottish side. They couldn’t cope with an extremely innovative approach of the Scots; the Scots could pass the ball – simple as that. England may have invented the modern game, but their neighbours invented the most crucial aspect of it.

An illustration of the first International Football Match

Football was very much an individualistic game back then. A player would stick to his position and would try to do things on his own. When English players came up against Scottish opponents, they would try to charge the holder of the ball, only to be outfoxed as it would be played towards an unmarked player. In the current context, it seems like a trivial tactical move; try telling that to the guy who invented the wheel. Scotland’s use of 2-2-6 also paved the path for development of the Pyramid system, the first universal football system.

Scotland’s style of playing short passes between themselves was soon picked by England. Football was changed forever. For the first time it had become a truly team game.

In a welcome move, the prestigious Home Championship will be revived from 2011.

River Plate (1941-1946)

In the six seasons following 1941, River Plate won 3 titles and finished second twice. The Argentine league was in its competitive zenith, which makes their achievement all the more remarkable.

The River Plate team of that era was known as “La Maquina”, The Machine. Staying true to the most popular system, they followed the “WM”. What made them remarkable was how frequently and easily the five forwards would switch their positions. This gave their attacking force a remarkable fluidity, confusing opponent defenders. Retaining attacking shape despite frequent interchanging of positions was one of the hallmarks of the ‘Total Football’. However, the Dutch phenomenon came a good thirty years after La Maquina’s peak, making them one of the first practitioners of the system.

Juan Carlos Munoz and Felix Lostau played as “outside forwards” (similar to today’s advanced wingers). Angel Labruna, one of the greatest ever goal scorers in the history of Argentine football, played as right inside forward, while Charro Moreno performed the duties of left inside forward.

Each of these footballers was blessed with terrific skills, but it was Adolfo Pedernera who added the X-factor. Pedernera was one of the earliest withdrawn centre-forwards in football. Nandor Hidegkuti would perform the same role for Hungary’s invincible team in the 50’s. By playing as a withdrawn forward, Pedernera freely exploited the open spaces between the opponent defence and River’s frontline. He was one of main contributors to Labruna’s impressive goal tally.

From left: Muñoz, Moreno, Pedernera, Labruna and Lousteau

Ernesto Lazzari, a star for River’s arch rival Boca Juniors once remarked – “I play against La Maquina with the full intention of beating them, but as a fan of football, I would prefer to sit on the stands and watch them play”.

River’s attacking force was so good that it kept a prodigious talent on the bench for most of his River career. The same player would migrate to Europe and become a legend there, Alfredo Di Stefano. Real Madrid’s talismanic player had picked up his trade from Moreno.

A wonderful read on La Maquina is here.

Tottenham Hotspurs (1961-1964)

“Super Spurs”. The team was called so, much to the dislike of manager Bill Nicholson, who thought the team could still better. Considering the achievement of Nicholson’s team, one can choose to disagree with the great man. Spurs became the first team in the 20th century to do “the double”, in 1961-62; and they did it in style, cheered on by a record 250,000 people over the season. Spurs scored a whopping 115 goals in 42 games. They amassed 66 points, matching the existing record.

Bill Nicholson took the movement started by Sir Arthur Rowe and Sir Matt Busby and took it to another level. English football suffered a rude awakening in front of the Magic Magyars in the 50’s. It was clear that the age old tactics of long ball will no longer work against continental opponents.

Nicholson encouraged individual flair, a rarity in English coaches. His tactics focused on swift interchange of passes. He also utilized a 4-2-4. It was a deviation from the traditional English game of launching crosses from the wings. Sir Alf Ramsey’s “wingless wonders” of the 1966 world cup would be the peak of the movement nurtured by Nicholson.

Dave McKay (left) and Billy Bremner (right) in a classic snap

The attacking trident of Les Allen, John White and Bobby Smith was propped up by crafty midfielders Danny Blanchflower and Dave McKay. Goalkeeper Bill Brown made many crucial stops throughout the season.

Spurs’ refreshing style of playing the game led them to considerable success in Europe. In 1962-63 Nicholson signed Jimmy Greaves from AC Milan. He strengthened the squad which dominated most of its games on its way to the semi-final. In the semi-final, Spurs put on an inspired display but lost out to Eusebio’s Benfica. However, they provided a much needed fillip to English Football, which was still suffering from the loss of the Busby Babes.

A year later, Super Spurs would go on to create history. They would become the first English team to ever win a continental trophy. On the final of the European Cup Winners Cup ’62-’63, they dismantled defending champions Atletico Madrid. They won 5-1, with Greaves scoring twice.

Switzerland (1937-1954)

Hellenio Herrara, the Argentine master who formulated the rise of an all conquering Inter side in 60’s, is often wrongly credited with inventing “Catenaccio”. In truth, Herrara’s team merely perfected the system. The origin of Catenaccio can be traced back to Switzerland and a certain Austrian coach – Karl Rappan.

Rappan didn’t have a perfect team; most of his players were technically inferior to the superpowers of world football. He had to devise a strategy which would maximize the abilities of his players. So he came up with a system, whose basic target was to crowd out the opponent in both attack and defence.

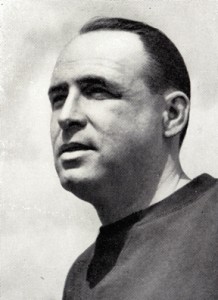

Karl Rappan, forgotten by time

When attacking, the “Swiss Bolt” would turn into a 3-3-4, with the attacking centre-half joining the forwards. The system’s defensive tactics would turn out to be more everlasting. When defending 8 to 10 players would retreat, outnumbering the opposition attackers. The centre-half would now become a centre-back, while the centre-back would drop to an even deeper position. This position would later turn into a “sweeper” in Catenaccio.

As it happens with pioneers, Rappan’s teams had very limited success with this system. It required a high level of fitness, so it wasn’t very popular in that era either.

FC Torino (1942-1949)

Some great teams cannot be measured by the number of records they have, yet some can be measured by the same yardstick. The legendary “Il Grande” Torino side of 1940s easily falls into the second category. Arguably the greatest club team of all times, they still hold most of the existing records in Italian football. They won a five back to back Scudetti, and still hold the records in terms of scoring most as well as conceding least goals in a single season. They also contributed a record breaking ten players to the Italian starting line-up.

However, their monumental records are just a tip of the iceberg. They were truly a one-in-a-lifetime team. In the 1958 World Cup, Brazil dazzled the world with an all-out 4-2-4 system. Torino had already used this system successfully in the previous decade. Their game was characterized by a late surge in matches. Legend has it that Valentino Mazzola, their charismatic leader, would roll up his sleeves in the 2nd half. This was a signal for the team, and they would surge ahead to destroy the opponent defence. Mazzola was one of the most versatile players of his generation. He could switch between attack and defense effortlessly, giving Torino’s formation a unique fluidity. He was ably supported by Guglielmo Gabetto, Aldo Ballrin and Romeo Menti.

The greatest club team in history of Serie A ?

Given Torino’s achievement in that period and the fact that their average age was in late 20s, it’s hard to imagine what they more could have achieved. Sadly, it was never meant to be. 4th May, 1949 would forever be remembered as the darkest day for Italian football. The entire Il Grande team, with their managers and club officials, died in a horrific plane crash. The team was returning after playing a friendly match from Lisbon. Due to poor visibility, the plane crashed against the wall of a Basilica on the Superga hill. There were no survivors, and the entire nation mourned an irreparable loss.

Both Italy and Torino would be crippled after the tragedy. Italy would endure shambolic world cup campaigns in ’50 and ’54, while failing to qualify for ’58. That is the only world cup till date that Italy hasn’t qualified for. Torino would suffer for decades, winning just one Scudetto in mid 70s. Valentino’s son Sandro would go on to become a legend in Internazionale.

Over the years, the Torino team has turned into an immortal myth. Half a century has passed since their demise, but fans still gather in the same Basilica on 4th May to pay homage to a great team.