The origin of football in India can be traced back to the mid-nineteenth century when the game was introduced by the British soldiers and sailors. While we have rarely been completely up to date with prevalent tactics of modern football, Indian football has gone through its fair share of tactical revolutions. In this series, we will make an effort to track down the tactical evolution of Indian football.

1) The Early Era – Profiling three great 2-3-5 teams.

2) First Revolution under Syed Abdul Rahim.

3) The tactical innovations of P.K Banerjee, Amal Dutta and Syed Nayeemuddin

4) Modern Era – New Generation of Indian Coaches and Foreign Managers.

The Early Era – Profiling three great 2-3-5 teams

The 2-3-5 or “Pyramid” is the mother of all football systems. It was the most commonly used system in the nineteenth century and remained popular till 1930s, when three modern thinkers of European football – Herbert Chapman, Hugo Meisel and Vittorio Pozzo remodeled the system. In India, naturally this system was used for a considerable length of time.

Note: In figures “dashed arrow” represents player movement while “solid arrow” represents passing.

Mohun Bagan (1911 IFA Shield Winning Team)

Mohun Bagan’s Immortal XI had been ignored by the mainstream media for a long time, before getting the deserved attention recently. However, the political and social aspect of their victory has been mostly highlighted (rightly so) and little spotlight has been given on the football aspect. Before discussing their formation and tactics in detail, let us first clarify what positions such as “right-out” and “right-in” signify. These terms are rarely used in modern football but a “right out” can be compared with modern version of advanced winger-forwards of a 4-3-3, while “right in” was more similar to the modern role of a support striker.

Bhuti Sukul, the right back, was originally a center-forward who played as a make shift defender. He would often fail to curb his attacking instincts and join the forwards – his tackling ability was top notch though. Sudhir Chatterjee, the only booted player in Bagan team, was a perfect foil to Sukul. The left-back was a bit slow but his sense of positioning was excellent and he rarely ventured forward.

The midfield had three contrasting players – an industrious runner, a tough-tackling snatcher and a creative player with sublime passing skills. Rajen Sengupta, who played as a center-half, was one of the fittest players in the team and covered every blade of the grass. He would often venture up to act as a sixth forward. Manmohan Mukherjee was an uncompromising tackler in midfield – he was nicknamed the “terrier” for his never say die attitude. He gave protection to Nilmadhab Bhattacharya –famous for his precise passing.

Mohun Bagan’s lineup for 1911 Shield Final

Shibdas Bhaduri not only assembled the team but was also the virtual manager of the team (the era of professional coaches was yet to begin). He willingly gave up the position of center-forward to Abhilas Ghosh. Ghosh possessed undaunted bravado and a tough physique – two essential requirements for a center-forward. Shibdas was the best dribbler in the team and was known as “Mr Slippery” locally. He was duly helped by Kanu Roy on the other wing – the fastest player in the team who launched precise crosses. Let us take a look at the tactical maneuvers they did in each match.

St Xavier’s (first round): Bagan played with ten men in this match as Sudhir Chatterjee was unavailable. Xavier defended well but was undone by lax defending on the edge of the box.

Rangers Club (second round): Bare feet Mohun Bagan players struggled to cope with the rainy conditions in this match. Shibdas Bhaduri did an unusual thing when he pushed Sudhir up. The booted left back gave stability to the midfield and was heavily involved in both goals as Bagan won 2-1.

Rifle Brigade (quarter-final): Brigade’s full-back Clarke was a tough tackler, who tended to pin wingers on the sidelines. To counter this, Kanu Roy was instructed to try and cut in from wings without crossing the ball. Roy dragged Clarke out of position and created space for Manmohan, who caused havoc in the opponent defense. The wingers didn’t send many crosses towards Abhilas, as Brigade’s ‘keeper Norton was an excellent spot jumper; instead they exploited latter’s weakness while countering low balls.

Middlesex Regiment (semi-final): Middlesex’s ‘keeper Pigott was a former player at Portsmouth and one of the best in Indian football at that time. Bagan’s front five struggled to beat him in the first match (1-1 draw) as well as in the replay. Unfortunately, Pigott got an eye injury and shipped in three goals in last ten minutes of replay. Shibdas and Bijoydas frequently switched positions in this match, confusing Middlesex defenders with their physical similarity.

East York Regiment (final): Whitney kept a close watch on Shibdas in the final, nullifying him in first half. To counter this, Shibdas instructed Abhilas Ghosh to stand in an offside position and get back into onside position when a ball was played. This confused the East York defense, and Shibdas started taking advantage of this by swapping positions with his brother. Manmohan Mukherjee was pushed up as sixth striker to bolster the attack, allowing Shibdas to drop back deeper and escape his marker. Shibdas himself scored the equalizer while he started the move deep from midfield which allowed Ghosh, who timed his run to perfection, to score the winner.

Amal Dutta, a veteran Indian coach, had seen the recording of the final in a documentary made by Madden Company – he said that Mohun Bagan’s play showed signs of well-planned tactics, which was a rarity among Indian clubs at that time.

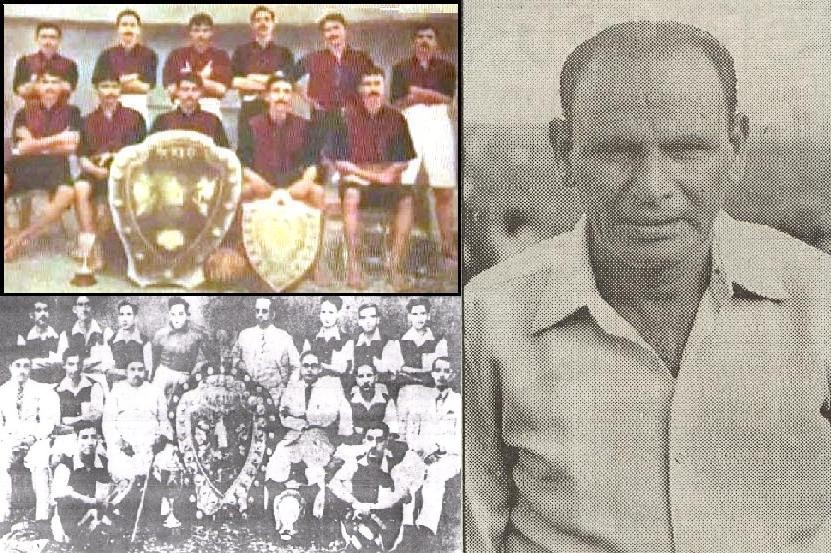

Mohammedan Sporting (Winners of five back to back CFL titles in 1930s)

The biggest strength of Mohammedan’s 2-3-5 was in its cosmopolitan nature. This ensured that players with different styles of play were amalgamated together to form a team which was unpredictable in nature. Another feature of Mohammedan was that they were one of the first Indian clubs to embrace the use of boots – thus nullifying a big advantage for British teams.

Osman Jan was one of the early exponents of a sweeper-‘keeper in Indian football as he would often venture out of his area to launch long balls towards the center-half. The Black & Whites were especially strong on the left flank where a combination ofTaj, Noor Mohammad and Bacchi Khan dominated the opposition in every single game. Another unique feature of this Mohammedan team was the deployment of Bacchi Khan as a left-out. In those days players who were fast, with good crossing ability, were usually used as “out” forwards. Bacchi Khan, contrastingly, was not known for his pace but for his fierce tackling. He would often terrorize opponent full-backs with his hard tackles – snatching the ball and setting up scoring opportunities for Rahim or Rahamat. Such a move was performed because of Bacchi Khan’s playing style, rather than a pre-determined tactics but it can be classified as an early example of pressing football in India.

The Invincibles of Mohammedan Sporting

The central trident of Rashid, Rahim, and Rahamat had perfected what the Bhaduri brothers started in 1911 – frequently switching their positions in a match. In terms of fluidity, the front five of Mohammedan Sporting can be called as an Indian version of River Plate’s famous La Maquina team of 1940s.

East Bengal (1949-1953, the Five Pandavas)

East Bengal enjoyed its first golden age under the stewardship of legendary Jyotish Chandra Guha. Guha began recruiting players from all parts of the country – focusing on the then football hubs of Mysore and Hyderabad. East Bengal’s front five were unstoppable in this period and went by the moniker of Panchapandavas.

Among the five forwards, M Apparao was the first to arrive at the club. The right-in striker joined Red and Golds in 1941. Left-out Saleh hailed from Kerala and was inducted into the club in 1945. P Venkatesh, right-out, who started his career in Bangalore, joined in 1948. J.C Guha completed his legendary team in 1949 with two of its most important players – Ahmed Khan and K Dhanraj. Thereafter, the East Bengal juggernaut began to role.

East Bengal lining up with Five Pandavas upfront

With its five strikers in top form, East Bengal became a prime force in Indian football – winning trophy after trophy. In those five years, East Bengal scored 387 goals – the front five accounted for 260. Centre-forward Dhanraj scored 114 goals, Venkatesh 71, Ahmed 35, Saleh 31 and Apparao 9. Bolstered by their frontline, East Bengal became the first team to complete a hattrick of Shield titles and also earned an invitation to play in Europe.

Ahmed Khan, a genius, was the lifeline of this team. Despite playing as a inside forward, he would often drop deeper, dragging defenders out of position and creating space for Dhanraj. Ahmed was, arguably, the first case of a withdrawn striker in Indian football. Another unique feature of this team was the style of Venkatesh, who would regularly cut in from the wings often acting as a make-shift inside forward. According the veteran journalist Mukul Bose, Ahmed’s versatility made East Bengal’s system extremely fluid. When they attacked, they did it with six players; while defending they always had four players at the back. Full-back Byomkesh Bose was well known for his long crosses which fed Dhanraj’s exceptional heading abilities. East Bengal also had an exceptionally strong midfield, in which industrious Chandan Singh Rawat combined seamlessly with combative Paltu Ray.

Another great 2-3-5 team that deserves a mention is the Hyderabad City Police team of 50s that captured five consecutive Rovers Cup titles. The man who coached that team Syed Abdul Rahim would eventually become one of the corner stones in tactical evolution of Indian Football.

(To be Continued…)

Sources: “Stories from Indian Football” by Jaydeep Basu. “Goal-less” by Boria Mazumdar and Kaushik Bandopadhyay. “East Bengal-Mohun Bagan Reshareshi” by Manas Chakravarty. “Ekadoshe Surjodoy” by Rupak Saha. Old articles in Khela Magazine and other news papers.

Follow the author in twitter @somnath_THT

Follow thehardtackle in twitter @thehardtackle